Newsweek: Behind-the-Scenes of Campaign 2004

How Bush Did It

This story is based on reporting by Eleanor Clift, Kevin Peraino, Jonathan Darman, Peter Goldman, Holly Bailey, Tamara Lipper and Suzanne Smalley. It was written by Evan Thomas.

Newsweek Exclusive: A team of NEWSWEEK reporters unveils the untold fears, secret battles and private emotions behind a historic election.

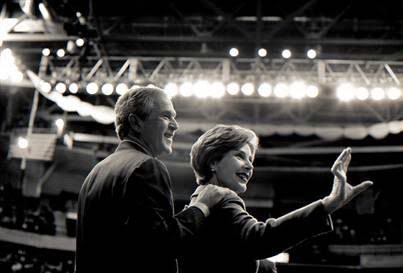

Charles Ommanney / Contact for Newsweek

The president and First Lady at a New Hampshire rally

Nov. 15 issue - In the winter of 2003-04, Jenna Bush, one of president Bush's 22-year-old twin daughters, dreamed that her father lost the election. Jenna had never before shown any interest in politics or much desire to get involved in her father's campaigns. But now she, along with her sister, Barbara, volunteered to help their father get re-elected. The president was overjoyed to have the girls on the campaign bus, recalled his wife, Laura. His mood lightened, to the relief of his handlers, who had been anxiously discussing their candidate's surliness and impatience.

Politics has been a family business, and a family war, since long before the Capulets and Montagues began plotting against each other. Alexandra Kerry, the Democratic nominee's 31-year-old daughter, disliked politics, but she campaigned hard for her father anyway, until one day hecklers called her a "baby killer." Weeping in her father's arms, she confessed her fear that the Republicans would steal the election. Kerry comforted her, telling her that he would not let that happen (just in case, his campaign recruited 10,000 lawyers).

For all the billions spent and the efforts to make elections a semi-science (Karl Rove, Bush's chief adviser, was always studying "metric mileposts" in his get-out-the-vote operation), politics is intensely personal. Presidential candidates are in some ways objects, screens upon which we project hopes and dreams, fears and hatreds. But they are also human—they are husbands and fathers, they have insecurities and doubts, moments of loneliness and fatigue. They are motivated to run for office by visions of a better country but also by old resentments and angers. This was especially true in the 2004 presidential election.

It is not clear when George W. Bush and John Kerry first met. Kerry once recalled Bush, none too fondly, to writer Julia Reed of Vogue magazine: "He was two years behind me at Yale, and I knew him, and he's still the same guy." Bush says he has no recollection of meeting Kerry at Yale. Both presidential candidates were members of the same college secret society, Skull and Bones, but brothers they were not. The two men had disliked each other before they knew each other.

Bush did not remember Kerry but he knew the type: sanctimonious suck-ups who looked down on fun-loving fellows like George W. Bush. In the world according to Bush, guys like Kerry were not out just to ruin Yale. They wanted to take over the whole country, to impose the smug, know-it-all liberal ideology on regular, God-fearing, hardworking Americans. Kerry's regard for Bush was just as dismissive. Kerry may or may not have met Bush at Yale but he had met his kind before. At Kerry's prep school, boys like Bush were known as "regs," regular guys, the cool, sarcastic in-crowd that made awkward, too-eager-to-please boys like John F. Kerry feel low and left out. The regs were insular, stuck up, too sure of themselves to reach out to, or even see, the wider world.

It is impossible to understand the 2004 presidential campaign without appreciating the nature of the animus between the two men. It wasn't entirely personal; the candidates were capable of saying gracious things about each other's family. But their differences went beyond party or ideology or styles of leadership. Each saw the other as a symbol of the wrong side of the great post-1960s divide. Bush eyed Kerry and saw the worst of Blue State America—a pseudo-intellectual, a Frenchified phony, a dithering weakling. Rove built a whole campaign around this point of view, casting Kerry as a "flip-flopper," "out of the mainstream," clinging to the effete "left bank" of society. Kerry looked down on Bush and saw the worst of Red State America, a know-nothing who blustered and swaggered, even though his head was stuck in the sand. The two candidates could debate lofty issues in a time of war, but their mutual disdain showed through.

Thanks to modern technology and the influence of money, Bush and Kerry could summon enormous resources to bash each other. The 2004 presidential campaign was the first $1 billion-plus campaign (up from roughly $600 million in 2000). About the only good thing that can be said about the cascade of money, much of it from special interests, flowing into the campaign was that it was probably a wash—a zero-sum game, a case of massive overkill on both sides. Both Kerry and Bush were able to call on some very clever political minds. Indeed, Kerry could not stop calling on them—he used his cell phone so much that his handlers twice took it away. Kerry's tendency to endlessly revisit decisions muddled his message. Often, he seemed so tangled up in dependent clauses that he lost sight of the larger issues facing the country.

Kerry (like Bush) is a far more complex man than the caricature he helped create. He could be decent, thoughtful, sensitive, especially with his well-loved daughters, Alexandra and Vanessa. He had proved his toughness and resilience in war and politics; he was a searching and careful thinker. And yet at times he seemed like a shallow opportunist with a finger in the air. Politicians, of course, need both vision and practicality to get anything accomplished, and Kerry, while often cautious, could also be bold. Both to heal the bitter partisan divide and because he would do anything to win, Kerry offered to make GOP Sen. John McCain a kind of grand national-security czar—serving as both secretary of Defense and vice president in a Kerry administration. McCain declined and supported Bush.

In an interview with two NEWSWEEK reporters aboard Air Force One in August, Bush was funny and relaxed, self-confident enough to be self-effacing. He is blessed with a patient and caring wife who can tell him when he has gone too far. Yet the peevishness that he showed in the first presidential debate was never too far from the surface. Bush may believe in himself too much. Or, more precisely, perhaps, he has banished his self-doubt to the point where he mistakes his own ego for the national purpose.

For more than a year, NEWSWEEK followed the presidential campaigns of both men from the inside. Beginning in mid-2003, a team of NEWSWEEK reporters detached from the weekly magazine to devote themselves to observing, recording and shaping the narrative that follows. The reporters were granted unusual access to the staffs and families of both candidates on the understanding that the information they learned would not be made public until this Election Issue—after the votes were cast on Nov. 2.

Viewed close in, the Kerry campaign was even more unwieldy and clumsy than it appeared in plain view. An underreported story of the campaign was the distracting presence of the candidate's willful wife, Teresa Heinz Kerry, who demanded everyone's attention, including her husband's. Kerry was delighted by Teresa, and not just by her fortune; she was smart, sexy and independent. But at times she could be a trial. Kerry himself was a loner, willing to be criticized but oddly impervious to criticism. The candidate was almost impossible to "manage," at least until the fall of 2004, when John Sasso arrived on the campaign plane to impose some discipline. It was a good thing Sasso came aboard with less than 60 days to go, observed Jim Jordan, Kerry's first campaign manager (fired after nine months in 2003); any longer and Kerry would have tired of him, too.

President Bush, by contrast to senator Kerry, was a zealot for order. The hard-drinking frat boy had long since found the cleansing joy of discipline. He demanded a tightly wound, top-down, on-time-to-the-minute operation. His advisers, some of them martinets, gave him what he wanted. At Bush-Cheney 2004 headquarters in Arlington, Va., the dress code was corporate and the atmosphere vaguely martial. Staffers were supposed to be upbeat at all times. The press was at best a nuisance to be tolerated. (Periodically, NEWSWEEK would be banished from campaign headquarters, the last time because the magazine reported that a couple of campaign staffers had been seen twirling their cigars at an "off the record" party before the first debate.)

Better organized than the Kerry campaign, more clever and quicker to respond, the Bush campaign became too confident, openly condescending toward the sometimes hapless Kerryites. It was almost too successful in creating, in the public mind, a caricature of Kerry as a loser. When, at the first debate, Kerry appeared more presidential than the president, the Bush campaign was stricken with near panic. It rallied by becoming even harsher in its treatment of Kerry. And Kerry slammed right back, as if to show he could mislead as shamelessly as his opponent. There were undoubtedly great issues of war and peace at stake in the election, but the attacks were highly personal, right up to the day the votes were cast.

Bush had the advantage of being a better natural campaigner than Kerry, who never did learn how to deliver a speech. Campaigning ground Kerry down; he seemed to labor under the weight of expectation. But Bush was worn by war and burdened by the terrible weight of the terrorist threat—and that was before he began stumping for re-election. Both men had deep reserves of grit and ambition. The ugly race did not necessarily reflect the character of the candidates. Both have a sense of honor, even if their better sides were sometimes hidden. In the end it was Kerry who had to find the moral fortitude to accept reality—and abandon a dream he had begun nurturing in high school.

Campaigning for the presidency is grueling beyond all imagining. It takes an extraordinary person to withstand the grind, the abuse or the pressure. Kerry and Bush, for all their human flaws and foibles, are not ordinary men. They are driven—by patriotism, duty, vanity, vision and, in this election, a lifelong disdain for each other. Each man saw in the other a world view he utterly rejected. Their personal differences, writ large, became the choice on Election Day, 2004.

Fits and Starts

The Democrats: John Kerry thought the nomination was his but didn't count on Howard Dean. He made a hard charge for the finish line as Dean's campaign imploded.

Why Kerry Isn't A Natural Politician

David Hume Kennerly / Reuters

Does Kerry have a passionate side, too?

Nov. 15 issue - John Kerry didn't want to get on his own campaign bus. It was just after Labor Day 2003, and the day before, Kerry had formally launched his candidacy with a forgettable speech, delivered while standing in front of an aircraft carrier in Charleston, S.C. Now, as he was preparing to leave a rally in Manchester, N.H., Kerry strongly objected to the slogan plastered on the side of the bus: COURAGE EQUALS KERRY. He was traveling with his Vietnam buddies, and combat veterans didn't like advertising themselves that way, he protested. Real warriors—men who have actually been shot at—don't care to brag, or even much talk about it. Kerry was in a funk. He stood outside the bus, refusing to get on while he complained about the posters advertising his personal courage. "You have to get on the bus," quietly insisted his top adviser, Bob Shrum. "I'll get on the staff bus," Kerry pouted.

His handlers had seen it before. Kerry did not like to play the brave war hero. His pollster, Mark Mellman, had tested a theme line—"John Kerry has the courage to do what's right for America"—and voters seemed to like it. But Kerry didn't. He was uncomfortable with showy displays of any kind, but especially ones that glorified his combat record. Jim Margolis, his paid media man, was eager to make ads using the almost three hours of film footage Kerry had shot with a handheld super-8 camera in Vietnam. The catch was that only about 15 seconds showed Kerry. "Goddammit, John, didn't you want to send anything home to your parents, for God's sake?" Margolis complained. Kerry answered, "No, that isn't what I was trying to do." He had wanted to capture his experiences—the countryside, the Vietnamese people, the ravages of war. Not to show off himself.

Kerry didn't want to talk about the war. And yet he seemed to talk about it all the time, constantly reminding voters that he (unlike most other politicians, including George W. Bush) had fought for his country. Evoking his war record had been his trump card at critical moments in his political career. (In his hotly contested '96 Senate re-election campaign, his opponent, popular Massachusetts Gov. Bill Weld, criticized Kerry's opposition to the death penalty. Kerry gravely intoned, "I know something about killing ...") Chris Heinz, Teresa Heinz Kerry's 31-year-old son who enjoyed a teasing, macho relationship with his stepfather, bluntly warned Kerry that the press was beginning to view Kerry's frequent evocations of his Vietnam service as a tired cliche. To some of Kerry's aides, the senator seemed almost bipolar about his war record: on the one hand, the strong silent type; on the other, living proof that the Vietnam War will never end.

To show off—or not? To be proud—or humble? To strut—or self-deprecate? Sometimes Kerry seemed torn by conflicting impulses, and not just about his war record. Like every politician, he yearned to be noticed. The wise guys of the Massachusetts media and political establishment made fun of Kerry for hogging the limelight: they called him "Live Shot." As a legislator he was not a backroom dealmaker. He liked to be out front, conducting high-profile investigations of hot topics like allegations of drugrunning by the CIA. And yet he was capable of small acts of modesty and decency, of giving credit to others, and he often seemed uneasy before a camera or a microphone.

Kerry's ambivalence helps explain why he is not a natural politician. Kerry cannot sit still. He must always be up and doing, and he has been running for president, depending on whom you believe, since he was 14 years old, 18 at the latest. He was mocked for his ambition ("JFK," it was said, stood for "Just For Kerry"). Yet his more perceptive schoolmates always sensed that he was listening to some inner voice, telling him not to give in to the siren song of self-promotion. It is the same stern, patrician voice—preaching modesty, humility, duty—that whispered into the ears of generations of privileged youth of the old WASP ascendancy, including generations of Bushes. "I do not want to hear the Great I Am," Dorothy Walker Bush, mother and grandmother of presidents, had scolded her son George if he bragged too much about his sporting triumphs as a schoolboy in the 1930s and 1940s.

Though Kerry liked to play down his elitist side—his accent, pure Thurston Howell III as a young man, became less plummy over time—he never shed all the trappings of his social class, or tried to. To his classmates Kerry had been a bit of an outsider, the fruit of some Brahmin seed (a Winthrop and a Forbes on his mother's side, but he learned only late in life that he was part Jewish on his father's side), and he was never as well off as most of his classmates. They thought he tried a little too hard to show that he really belonged and, by striving, betrayed his insecurity. The WASP ascendancy was beginning its decline when Kerry graduated from the poshest of the New England prep schools, St. Paul's, in 1962, but its gentleman's code of muscular Christianity was still strong. Episcopal Church schools like St. Paul's tried to teach the virtue of humility, the sin of pride, the value of quiet service to others ...

That is, up to a point. Ruling-class sons were supposed to compete hard—but not sweat too much. To get (or stay) ahead—but do so gracefully, even effortlessly. To wear the mantle of wealth and power lightly, coolly. The style had been set by an earlier generation of swells who had fashioned certain unwritten, strict yet ambiguous rules of decorum. It was all very complicated, a tricky, delicate business of flaunting it, but subtly, and John Forbes Kerry, at least in the critical eyes of his classmates, never seemed to get the balance right. While other preppies had been perfecting their slouches on the greenswards of country clubs, Kerry had been grimly learning a more Puritan code, like how to navigate a small boat in the fog off the New England coast, doggedly trying to please his dour and secretive father. His mother sweetly preached the duty to serve and the old-time virtue of choosing the harder right over the easier wrong. (Her last words to her son, says Kerry, were "Integrity, integrity, integrity.") Their son was a good boy at school, a striver and serious, delivering a speech on "The Plight of the Negro" and founding a debating society. But he was too earnest, too obvious for the cutups, who mocked the faint air of superiority that Kerry wore, mostly as a defense.

Kerry's revenge was to do better, to excel, to leave his detractors behind—but not to boast! Never to gloat! Unless, of course, boasting was absolutely necessary to get ahead. There was something a little desperate, but admirable, about Kerry's determination. He would do what it took to get where he wanted to go.

In New Hampshire that day after Labor Day 2003, he got on the bus.

Kerry had been assured that the nomination was his, almost, as it were, by right. A memo drafted by his campaign manager, Jim Jordan, in November 2002 assured him that he would be "the first one out of the box" in the upcoming campaign and that he would raise the most money "because you're the best candidate." He would establish himself as front runner, soak up endorsements and contributions and march inexorably to the nomination.

It was all myth. Former Vermont governor Howard Dean, blunt and down to earth (especially in comparison with the lordly Kerry), had burst from the pack with a grass-roots Internet-fueled campaign and huge outdoor rallies on his Sleepless Summer tour in August. The establishment press swooned over the anti-establishment candidate. Kerry was deemed a hopeless stiff, his campaign written off as moribund.

Kerry was nonplused by it all, a little hurt that Dean had run as the "movement" candidate against Kerry, the tool of the Washington status quo. Kerry had been in the Senate for 20 years, but he still saw himself as the reform-minded antiwar protester who had come from Vietnam, tossed away his ribbons and defied the Nixon administration. (Dean had fun with Kerry's self-righteousness; at his private debate prep, he would pose as Kerry, sticking his nose up in the air and mimicking Kerry: "I was in Vietnam; I don't take any PAC money.")

Kerry didn't know what to do about Dean. His own advisers were divided. Most of the pros, his paid political consultants and campaign manager, wanted to go negative. The philosophy of Chris Lehane, one of his media advisers, was "You either hit or you're being hit." The hawks wanted to go at Dean from the left, to convince voters that Dean was not a true liberal. "We didn't want to rip the guy's face off," said Jordan, "but he wasn't going away, and we had to strip at least a third of his liberal support away."

Shrum and Jordan

On the other side, leading the so-called pacifists, was Kerry's most important adviser, Bob Shrum. Shrum is the brand name among big-money Democratic campaign consultants, the most-sought-after hired gun, brilliant and fluent but also insecure. He was Kerry's friend, his peer; everyone else was Kerry's employee. Staffers crossed Shrum at their peril. Edgy and superstitious, Shrum prefers, in tense moments, to wear a fuchsia scarf given to him by Washington superlawyer Robert Bennett—even in the middle of summer. He had forgotten to take his lucky scarf to Nashville on election night 2000, and he wasn't going to make that mistake again. Shrum had worked on the successful political campaigns of a third of the U.S. Senate. But when it came to presidential politics, his luck had generally not been good. He was 0 for 7 (his past clients included Ed Muskie, Ted Kennedy, Bob Kerrey, Dick Gephardt and Al Gore).

Shrum was a gifted wordsmith, the inheritor of the Sorensenian mantle, crafter of lofty phrases and speeches filled with the lift of a driving dream (which, after a time, started to sound alike, no matter whose lips uttered them). He had written Ted Kennedy's famous "Sail against the wind" speech in 1980, and politicians had lined up ever since, hoping that Shrum could make them eloquent, too. Shrum wanted to ignore Dean and take the high road with a series of "Great Speeches" about the future of the country. It was somewhat uncharacteristic for Shrum to argue against slashing attacks; he was known for taking a "people against the powerful" populist line. But his intuition told him that by demolishing Dean, the Kerry camp would only open the way for a late surge by Sen. John Edwards of North Carolina, a young but honey-tongued populist with a seemingly boundless future. (In the so-called Shrum primary, Kerry and Edwards had vied for the services of the superconsultant; Shrum had initially leaned toward Edwards.) When Team Kerry met in the summer and fall of 2003, Shrum acidly undercut the hawks who wanted to trash and burn Dean. "What do you want to do?" he asked. "Elect Edwards?"

For months, as Kerry sank in the polls and Dean soared, the argument rattled on inside the Kerry camp. Campaign manager Jordan had worked for Kerry for five years, serving as staff director of the Democratic Senate Campaign Committee when Kerry was its chairman. A soft-spoken but hard-nosed operative from North Carolina, Jordan admired Kerry, but he was weary of his indecisiveness. "The world around Kerry is a lot of white males talking," he groused. Every time Jordan decided something, the person who lost out went behind his back to appeal to Kerry, who spent inordinate amounts of time on his cell phone not resolving various disputes. Kerry was known for being deliberative—he was proud of it—but Jordan despaired that Kerry had been turned into a caricature of the U.S. Senate. Kerry's didactic, overlong speeches, his insistence on explaining every nuance of his rational thought process (while not revealing much of his true feelings), reinforced his image as a windbag. Jordan was blunt with Kerry, telling him that voters in focus groups said "they don't understand you, you won't shut up, you sound like a politician."

For the Labor Day announcement speech, the hawks presented a draft meant to be sharp and punchy, with lines like "Spring training is over" and "My mother was an environmental activist before it was cool." Shrum dismissed the speech as "sophomoric." At midnight before the speech, Shrum arrived at Kerry's house in Boston—he had taken a two-hour cab ride from Cape Cod—to insist that his speech be used, untouched. Kerry ended up giving Shrum's speech—"flowery bulls--t," according to Jordan. The reception was at best ho-hum.

Kerry was fading fast. The press got wind of the infighting and began joking that Kerry's campaign was like Noah's Ark—two of everything—as Kerry straddled the advice given him and tried to please everyone. "I couldn't get the man to make decisions," said Jordan.

By November, however, Kerry was finally getting ready to make one decision: to fire Jordan. As early as July, Kerry had approached his political mentor, Ted Kennedy, and asked his advice about replacing Jordan. Kennedy told him he thought a change was long overdue. Kennedy was an avuncular figure to Kerry. In an interview with NEWSWEEK in June 2004, Kerry went on and on about how he had studied Kennedy, a legendary storyteller and schmoozer, trying to learn from the senior senator from Massachusetts (40 years in office) that in the end it was "the people" that mattered, not so much one's policy views. But Kerry was uncomfortable with personal confrontation. He kept giving Jordan more rope. In the end, Jordan hanged himself.

The campaign manager's first mistake was to underestimate the Internet revolution of the Deaniacs. "There are no votes on the Internet," Jordan had said back in the spring of 2003. At a meeting of top staffers and advisers at Kerry's house on Nantucket over the Fourth of July, Kerry asked for a show of hands. How many thought Dean had crossed over from fringe candidate to serious contender? Only two or three people had raised their hands. One was Kerry himself. The candidate may not have been a natural politician, but he was able to spot the power of the Internet, particularly as a fund-raising tool, before most of his advisers did.

Jordan's second fatal error was more personal. He alienated the candidate's family. Kerry is something of a loner; unlike most presidential candidates, he does not have a longtime political consigliere or friend who regularly travels with him on the plane. His only consistent adviser was his brother, Cameron, a Boston lawyer, a low-key figure who was devoted but not politically savvy. Jordan did not have much use for Cam. "He's no Robert Kennedy," said Jordan, and to Kerry, bluntly: "Keep your brother out of my way."

Kerry bridled at Jordan's impertinence, and he was especially protective of his wife, Teresa, who often clashed with Jordan. Teresa could be an earth mother, warm and funny, sometimes in an oddball way, and embracing to her friends and family. She liked to hand out her recipe for "Mama T's brownies" (she has 26 godchildren, who call her Mama T). But, in the manner of the very rich, she had an air of entitlement, a sharp temper, and she was known for keeping people, including her husband, waiting. The staff regarded her as something of a hypochondriac, and she canceled three trips in October—to Arizona, Pennsylvania and New Mexico—at the last minute, usually for what was described to aides as a "nonspecific malady."

Kerry seemed to be walking on eggshells around Teresa. He wanted her to be happy, in part because she was much more trouble on the campaign trail when she was unhappy. Teresa had a way of letting everyone know that Kerry was her second husband, and that she still loved her first, Sen. John Heinz, who died in a plane crash in 1991. (The portraits of the two Johns hang side by side in her Georgetown mansion.) Teresa above all valued her own candor. She wanted to be able to talk about her Botox injections and yak with women reporters about her views on reincarnation and the pros and cons of hormone-replacement therapy. She did not want to hear about "message discipline." Indeed, her frankness could be refreshing. Some crowds responded with "you go, girl" enthusiasm when she made fun of her husband and voiced a strong opinion on the trail. But others wondered why the slightly eccentric woman introducing the candidate was prattling on about herself in a difficult-to-understand accent. She was not one for the plastic, adoring smile of the traditional candidate's wife. On the other hand, Kerry's handlers wondered, did she have to look sullen?

At one point in the summer, as Dean was starting to pull away, Teresa called Jordan and demanded, "I want you to issue a challenge for me to debate Howard Dean." Jordan was less than diplomatic in telling her it was a crazy idea, and he had a little too much fun sharing the moment with other campaign officials. Jordan's e-mails trashing the candidate's wife, or word of them, inevitably reached his rivals—including Bob Shrum. An old friend of Teresa's from the Georgetown chattering-class party circuit, Shrum understood her moods and saw her importance to Kerry. Teresa and Shrum enjoyed drinking vintage wine together and commiserating about Jordan, sealing his fate.

Bouncing Back From a Campaign Meltdown

Late-night comics liked to joke that Kerry had married Teresa for her money to pay for his presidential race. (Jay Leno: "[Kerry] once raised $500 million with two words: 'I do'.") But, in fact, Kerry had signed a prenuptial agreement that kept almost all of Teresa's fortune (inherited from her first husband, the Heinz ketchup heir) in her hands. Under the campaign-finance laws, Teresa could give the Kerry campaign no more than any other donor—$2,000. True, the system is full of loopholes. Teresa could have found a legal dodge to use her vast fortune to help Kerry—she could have established some kind of trust in his name—and, indeed, she had vowed to spend her money if Kerry's opponents tried to destroy his character. But the "optics" of such a move, as the media consultants liked to say, would be terrible. It would vindicate all those late-night jokes about Kerry as a kept man.

Kerry would have to find some other way to raise the money to pay for his campaign. He had been virtually broke when he married Teresa. He was confined by the campaign-finance laws, which matched what a candidate could raise by private sources up to $18.7 million, but put a cap on spending in each primary state ($729,000 for New Hampshire, $1.3 million for Iowa).

Kerry had been a strong supporter of campaign-finance reform, but like any presidential hopeful, he envied George W. Bush—who, as a candidate in 2000, had raised so much money he didn't need matching funds from the Feds. A candidate could opt out of the campaign-finance system—"bust the caps," in campaign jargon. With his Internet money machine, Howard Dean was on track to raise more than $50 million before the first primary, and in November he decided to abandon the federal campaign-finance system so he could spend it all. On Nov. 6 and 7 he held a laughable Internet "plebiscite" to get permission from his faithful Deaniacs (most of whom were pro campaign-finance reform but were willing to put aside their scruples to win).

Jordan had been trying to conserve Kerry's money so that there would be enough left to buy ads after the primaries began. Shrum was agitating to spend more money on TV advertising, and he wanted to bust the caps. Shrum's partner, Tad Devine, put it to Kerry. Devine, a seasoned political hand who had effectively run the Gore campaign in 2000, was known for being willing to speak truth to power. In late October, Devine told Kerry: get out of the campaign-finance limits or get out of the race.

Kerry seemed to be "hand-wringing and dithering," said Jordan. "John's not an instinctive politician. He doesn't understand the rhythms of a campaign. He's a very gifted man in ways that are more analogous to being a good president than a goodcampaigner."

In fact, Kerry was following a familiar path on the campaign trail. A lackluster beginning—and, just as it seemed to be almost too late, a hard charge for the finish line. On Saturday, Nov. 8, he summoned Jordan to Boston and fired him. Kerry started by flattering Jordan, but then he insisted that Jordan resign and tell people it was his idea. Jordan refused, and the frustrations bubbled up. ("We did plenty of screaming at each other, and toward the end the 'f--- yous' got kind of loud," said Jordan.) The same day, Kerry opted out of federal financing and began the arduous business of trying to raise tens of millions of dollars and to resuscitate a campaign that was widely regarded as doomed.

First came some discipline. Ted Kennedy's no-nonsense chief of staff, Mary Beth Cahill, took over as campaign manager. (She had been watching the campaign, she said, with a "horrified fascination.") Cahill, white-haired and matronly in a steely sort of way, shut off the back channels to Kerry by turning off his cell phone and letting it be known, like a nun rapping knuckles, that she would not tolerate any more petty bickering.

Then came a marked improvement in the candidate. Kerry's speechwriter, Andrei Cherny, had been trying to think of a way to convey that Kerry was ready to go toe to toe with President Bush on national security, the Democrats' weakest front. The expression "Bring it on" popped into his head. He wrote the line into a Kerry speech to be delivered to the Democratic National Committee in October, but Shrum crossed it out. "Bush-type bravado," he sneered—too undignified for Kerry.

But with the press reporting his campaign in meltdown, Kerry needed to do something to change his soporific style, and at the Jefferson-Jackson Day dinner in Des Moines on Nov. 15, he used Cherny's "Bring it on" line. The crowd loved it. (Kerry later apologized to Cherny for not using the line earlier. "I was wrong," he said. But a few weeks later Cherny was purged by Shrum as a Jordan holdover whose punchy style did not suit the candidate.)

Strong, crisp—and presidential—Kerry was a hit at the JJ dinner, an important annual rite and showplace for the candidates. Kerry's campaign packed the crowd with supporters chanting "Real deal," Kerry's latest slogan (the real deal: that is, a candidate who could win in November, unlike Dean). It was a sign, if anyone had been looking, that Kerry should not be counted out. There were other omens that the race was far from over. Before the dinner, a curious event took place. The Dean campaign, eager to show off its vast army of Deaniacs, took reporters out on the skywalk in downtown Des Moines to watch 40-plus yellow schoolbuses rumble into town—shock troops in the Dean onslaught to get out the vote for the January Iowa caucuses, the first electoral test on the road to the nomination. One of the reporters noticed something odd. "Is it just me, or are they empty?" asked Liz Marlantes of The Christian Science Monitor. The other reporters tried to peer through the tinted-glass windows. All they could see was row after row of empty seats.

But in New Hampshire, Dean's polls continued to soar, while Kerry's remained flat. The press had already begun to look for someone else to play the role of spoiler to Dean, maybe Gen. Wesley Clark, who had entered the race late (in September), stumbled about as a campaign neophyte, but still held allure for Democrats paranoid about their own perceived weakness on national security. The capture of Iraqi strongman Saddam Hussein on Dec. 13 made Democrats despondent. Iraq was looking like a worthy cause after all; the violence seemed to be abating there. Bush looked invincible. Actually, Saddam's capture was good news for Kerry: it helped remind Democrats that in the end the nominee had to be electable, and that Dean was too far to the left and Clark was unready for the national political stage.

All this would become clear—in perfect hindsight. On Dec. 9 Al Gore showed the political fingertips that lost him the 2000 election. He endorsed Howard Dean, probably at the precise moment when Dean had peaked and was about to head down. Gore's endorsement came as a blow to Kerry, who had thought Gore was his friend, or at least his political ally. When the Kerry camp heard the rumors that Gore was endorsing Kerry's opponent, Kerry tried to call the former veep to find out if it could be true. Kerry had Gore's cell-phone number and called him. "This is John Kerry," he said when Gore answered. The phone went dead. Kerry tried to call several more times and never got through. He was hurt. "I endorsed him early. I was up for consideration as his running mate," he complained to an aide.

Kerry's revival was underway, slowly—imperceptibly to the press and the political establishment. Back in September he had made the brave—and difficult—decision to bet most of his resources on Iowa, not New Hampshire. Kerry had been expected to do well in his neighboring state, but he was getting drubbed by Vermonter Dean. (One poll showed Dean at 45 percent in the Granite State, Kerry at 10 percent; nationally, Kerry was about even with Al Sharpton.) He needed to do something to change the dynamic. He needed to win somewhere else.

Polling for the Iowa caucuses is notoriously difficult: it is hard to measure whether people will actually show up in the middle of January to spend two or three hours to cast their votes. But Kerry's pollster, Mark Mellman, had begun to notice that on a comparative basis, Kerry was doing better versus Dean in Iowa than in New Hampshire. The only way to come back in New Hampshire, he reasoned, was to create a slingshot effect, to pick up enough momentum in the Iowa caucuses to convince New Hampshire voters, who went to the polls a week later, that Kerry was the only electable candidate. "Iowa is the key to New Hampshire," Mellman told the Kerry team.

That meant shifting the campaign's limited resources to Iowa—in effect, to bet it all on the quirky Iowa caucuses. There was really no choice, argued Mellman. "There are two things we could do in New Hampshire," he argued at a strategy meeting in September. "One, we could save a drowning child in the Merrimack River [which runs through southern New Hampshire]. Second, we could have him [Kerry] do well in Iowa. The second is easier to arrange."

Kerry was persuaded, but barely, and by December he was having second thoughts. Losing New Hampshire would be a painful humiliation for him. "We need to be in New Hampshire," he would say. He was gambling more than his name. He had taken a $6 million mortgage on the house in Boston to bring some desperately needed cash into the campaign. (Under the prenup, Kerry had part ownership in one of Teresa's five houses.) His brother, Cam, worried that Kerry was betting his daughters' inheritance in a game he could not win. In early January, Kerry's best friend from school days and his former brother-in-law, David Thorne, called Shrum and asked if Kerry really had a chance of winning. "If it looks hopeless," said Thorne, "let's talk about it so he can stop spending his own money."

Shrum knew it wasn't hopeless because he knew Kerry. He understood that at just such moments Kerry had a way of rallying, of rising to the challenge, of even enjoying the sensation of risk and trying to control the uncontrollable. The staid, buttoned-up Kerry concealed a more passionate, audacious side. Shrum, a romantic, had been drawn to the Kennedys as a young theology student/law graduate turned politico. Kerry was not JFK—Kerry's own idol as a teen—but the similarities were more than superficial. Both JFKs liked fine and stylish people and things, thought deeply about history and the world—and were not afraid of risk.

Kerry does not like the daredevil label. He emphatically rejected it in an interview with NEWSWEEK, saying that he avoided really dangerous sports (he mentioned bungee jumping) and was always in control when he took on scary-seeming physical challenges, like kite boarding (a kind of airborne windsurfing). But control is a relative thing, and Kerry clearly likes to look for the edge. For instance, he said he performed aerial stunts only in a plane above 5,000 feet, so that if something went wrong, he'd have time to parachute.

Before Christmas, Shrum drove back to Boston from New Hampshire with John and Teresa and stayed at the house on Louisburg Square, the one Kerry had mortgaged, an elegant brick mansion in the old Brahmin quarter of Beacon Hill. It was snowy outside, and the old friends opened a bottle of wine and began reminiscing. They recalled an earlier crisis, in the fall of 1996, when Kerry had been faltering in his Senate re-election race against Governor Weld. Kerry had invited Shrum to dinner and asked him to take over the campaign. He had shoved a poll across the table and said, "We're behind in 14 of the 15 internals"—the important polling benchmarks on questions like "Who do you trust more?" and "Who is a better leader?"

With Shrum's help, Kerry had rallied in the '96 Senate race, as he always had, and beaten Weld cleanly. "I've been in tougher situations than this before," Kerry said that snowy evening, as he, Teresa and Shrum sat around sipping their good wine in front of the fire. Shrum knew that Kerry was thinking about Vietnam. "When he's in a tough situation, he thinks at least they're not shooting bullets," says Shrum.

Shrum had taken some more tangible comfort from his friend the pollster Stan Greenberg, who believed that the voters of Iowa would inevitably take a second look and ask: Who is presidential? Who can take on Bush? Kerry needed to be there, front and center, because the answer would not be Howard Dean.

The Dean Campaign Implodes

Paul Sancya / AP

Dean: The meltdown moment

Few people knew it at the time, but the Dean campaign was imploding. The Deaniac movement had been in large part a creation of political grass-roots mastermind Joe Trippi. A creative genius, Trippi did not sleep and appeared to live on Diet Pepsi, consuming at least a dozen a day. Pepsi cans were strewn around his office and arrayed along his desk, where the empties were used as receptacles for wads of Skoal chewing tobacco. ("This campaign is all about getting me a gig as a Pepsi spokes-man," he quipped to a reporter.) He had once fallen asleep while standing and hit the floor with such force that he cracked a rib. Trippi's caffeinated rages, fueled by his off-the-charts blood sugar (a diabetic, he was dangerously careless about taking his medications), reduced his assistant to tears. Once, after he overturned his desk, she fled out the door and did not return for three days.

Dean was in some ways the accidental candidate. Truth be told, he wasn't really the red-hot revolutionary of the Deaniacs' fevered hopes. He was a moderate, fiscally conservative small-state governor who had been swept up in a wave not entirely of his own making. He and Trippi never worked well together. Dean was a micro-manager who refused to give Trippi control of the campaign checkbook. Management was not Trippi's strong suit; the campaign, badly run, burned through its $40 million war chest. By October, Dean and Trippi were speaking to each other only when they had to, and Trippi was threatening to quit.

The closer Dean came to actually winning the nomination, the more he seemed to misstep, to blurt out something that the gaffe hunters in the press could hang around his neck. Dean had always been a loose cannon. In the summer of 2002, his aides had been relieved that no cameras had captured the would-be Democratic nominee, in full cry at a gay fund-raiser on New York's Fire Island, shouting out, "If Bill Clinton could be the first black president, I can be the first gay president!" But now the press was circling, and he seemed to recoil. In December, Trippi told his aides, Dean had come to him and tearfully confessed that he had run only to shake up the Democratic Party and push for health-care reform, that he never cared about being president and never thought he could win. ("That's a figment of Joe's imagination," Dean told NEWSWEEK. "I mean, Joe just made that up out of whole cloth.")

By then Trippi's loyalty really lay less with Dean than with the cybermovement he had built. Dean was irritated by Trippi's celebrity (the campaign manager was often wired for a CNN documentary and had to be reminded to turn off the mike when he went to the bathroom). By early January, Trippi was in a deep gloom, and so were his closest campaign associates. One senior aide compared the Dean campaign to the novel "Flowers for Algernon," the story of a seriously retarded man who, put through a course of radically experimental treatment, lives for a few months as a genius—then regresses rapidly to what he had been before the experts remade him: a moron.

Trippi was planning on retiring to his farm in Maryland after the New Hampshire primary. Still, he wanted to take one last shot, to "bet it all" on Iowa and New Hampshire, knowing that in a protracted fight Dean's candor would kill him. "It's probably a f---ing miracle we're even sitting where we're at," he said, utterly despond-ent. He fell silent for a while. "The guy," Trippi said suddenly, referring to Dean, "is not ready for prime time. I mean, he's just f---ing not ready for prime time, and he never will be." There were 11 days left before the Iowa caucuses.

Dean's plan in Iowa was to flood the state with an army of volunteers, in jaunty orange caps, to knock on doors and personally escort voters to the polls. Kerry's Iowa organizer, Michael Whouley, was appropriately skeptical of the Dean approach in small rural towns where out-of-state college kids were regarded as aliens. A legendary political figure who avoided most reporters (thus enhancing the legend), Whouley was patient and quiet, but he had an aura of confidence. On the Friday night before Christmas he gathered 80 field staffers in a Unitarian church in downtown Des Moines and told them, "It's never a guy with the early momentum. It's the guy with the late momentum, and that's us."

As he crisscrossed Iowa, Kerry was a much more engaged and relaxed campaigner. He seemed bemused and affectionate with Teresa, not quite so nervous about her mood. "C'mon, General, let's go," he said, patting her on the back and marching her onstage at a campaign event in Iowa in early January. He told the women in the room that he wouldn't see his wife again until after the caucuses; the ladies made an "awww" sound. Teresa smirked and made a "no big deal" gesture.

The traveling press continued to have doubts about Teresa. After one particularly disjointed speech at the Hotel Fort Des Moines in early January, press aide David Wade paced nervously while reporters snickered that the candidate's wife was on medication. But the press was warming to Kerry. He had begun traveling with an old friend from his antiwar days, Peter Yarrow of the folk group Peter, Paul and Mary. Kerry had played bass in his prep-school rock-and-roll band, and to relax he liked to strum a guitar and sing along with Yarrow. The old folkie seemed to make Kerry nostalgic and remember his roots as an authentic movement figure. (When Yarrow played "Puff the Magic Dragon," a CBS camera caught Kerry playfully miming that he was toking on a joint.) On one frozen night, heading down desolate Route 63, an exhausted Kerry and his staff and the traveling press passed out cold Budweisers and chocolate cake. "Pedro," Kerry said, "get your guitar." Late into the songs, Yarrow played "Carry On My Sweet Survivor":

Carry on my sweet survivor

Carry on my lonely friend

Don't give up the dream and

Don't you let it end

"Was the struggle worth the cost?" Yarrow asked Kerry. "Yes, Peter, it was," said Kerry softly. Even the most jaded reporters sat quietly for a moment.

Despite Kerry's uneasiness over playing up his war exploits, the campaign had been airing an ad showing one of his old Swift Boat crewmen, Del Sandusky, saying that Kerry's boldness and decisiveness had "saved our lives" in Vietnam. Here was the way to get around Kerry's reticence: have his crewmates speak for him. The ad was a success. Iowa voters who had seen the ad favored Kerry by almost 20 points.

The best testimonial came by pure luck. In Oregon in early January, a retired policeman named Jim Rassmann was in a bookstore and noticed a book about Kerry's Vietnam experience by historian Douglas Brinkley, "Tour of Duty." Rassmann had been a Special Forces soldier who had fallen off Kerry's boat during a fire fight in the delta. Kerry had swung his boat around and come back to rescue Rassmann. His arm injured, Kerry himself had pulled Rassmann out of the water. Rassmann thumbed through the index of "Tour of Duty" and saw his story. On a whim, he called the Kerry campaign and said he'd like to help. The receptionist, Jackie Williams, had the presence to get hold of the campaign's veterans coordinator. Rassmann was in Iowa the next day, flown there by the campaign. (Briefing Rassmann, a Kerry aide asked if he'd ever been in front of cameras. "Yes, usually after somebody's been killed," the ex-cop drolly replied. He had worked as a homicide investigator.)

Kerry was genuinely surprised to encounter Rassmann, whom he had not seen since 1969. Their reunion, a warm hug, was on television all over the state. The caucuses were only two days away.

On caucus night, as they were riding in a darkened bus in Des Moines, a Fox News producer handed Shrum the entrance polls. Kerry 29, Edwards 21, Dean 20, Gephardt 15. Shrum later recalled that he felt like crying. He showed the numbers to Kerry, who extended a wordless high-five.

The race was, for all practical purposes, over. The Dean scream, uttered a few hours later as Dean tried to rally his crestfallen troops, was mostly theater; the damage had been done. Dean had finished with 18 percent of the vote at the Iowa caucuses. The press, and most Democrats, wrote him off. Edwards would make a good showing in the primaries ahead, but he didn't have the money or the presidential gravitas to overtake Kerry.

Kerry was in the shower the next week when he won in New Hampshire, the state that had seemed so hopeless only a month before. With the campaign short of funds, he had been staying at the Tage Inn in Manchester, a bare-bones establishment, and on some mornings the showers had run cold. On primary night the hot water was working, and Kerry was enjoying it, leaving the bathroom door ajar so he could hear the television. Shrum and Teresa were in the room watching when ABC called New Hampshire for Kerry. There was a shriek from the shower. "Oh, God, I've won the New Hampshire primary!" he yelled. For once, Kerry let himself gloat.

The President: Bush's team was upbeat. But not everyone was sure about the race.

The Campaign for a Second Term

Nov. 15 issue - Karl Rove called the group "the Breakfast Club." They met at Rove's unadorned house in northwest Washington on Saturday, Dec. 13, 2003, the day Saddam Hussein was captured in Iraq. It had already been a week of cheering news for the Bush-Cheney 2004 campaign. A few days earlier, former vice president Al Gore had endorsed the Democratic front runner, Howard Dean. The Democratic establishment seemed to be lining up behind Dean. The Bush-Cheney campaign could only pray that the Democrats would not come to their senses. Rove's team had already assembled a phone-book-thick volume of opposition research on Dean, titled "Howard Dean Unsealed: Second Edition, Wrong for America" (on the cover was a collage of 13 pictures of Dean looking addled). The Bushies had been poring over footage of the former Vermont governor on the campaign trail. Adman Mark McKinnon's media team had cut a spot called "When Angry Democrats Attack!" featuring a wild Dean ranting and raving, and posted it on the Bush-Cheney Web site.

Rove had called this meeting of his top advisers to discuss all the ways they were going to bury Howard Dean. Matthew Dowd, the campaign's pollster and strategist, was known as a pessimist, but even he conceded to the group, "You have to give the direction arrow to Dean at this point."

The strategy was obvious: a barrage of ads featuring President Bush as "steady" and Dean as "reckless." The group laughed about some of the scripts they had cranked out for a campaign McKinnon was calling "Dean Unplugged." An early favorite, submitted by Fred Davis, a California adman known by the nickname Hollywood (he drove a Porsche, wore tinted sunglasses and had shared a suite in college with Paul Reubens, the actor better known as Pee-wee Herman), opened with the image of a mother anxiously flipping channels as her baby lies in a crib behind her. Howard Dean is on the TV screen, hyperventilating. The baby begins to fret and cry ... then the voice of George W. Bush, strong, comforting, resolute, replaces Dean on the screen. The baby quiets and sleeps peacefully.

It was an open secret that Karl Rove was itching to take on Dean. Back in July, Rove had been seen standing in a crowd near his home in Washington, watching Dean pass by in an Independence Day parade. Rove was quoted as chortling: "Heh, heh, heh, that's the one we want. Go, Howard Dean!" Misquoted, Rove insisted to NEWSWEEK (the witness, he claimed, was a "lefty," a Sierra Club member). Rove said he simply joined in the chanting, "Two, four, six, eight, why don't we all bloviate!"

"Bloviate" is a favorite Rove-ism. Others, often expressed by e-mail: "Yeah baby!" "Attawaytogo!" and, more obscurely, "It's Miller time!" Rove was the unquestioned boss of the campaign to re-elect the president. Everyone reported to him; even local GOP bosses checked with him before making a move. The group he gathered around his dining-room table this December morning was the tight little inner circle—Dowd, campaign manager Ken Mehlman, White House Communications Director Dan Bartlett, campaign Communications Director Nicolle Devenish. The group was secret at first; other top staffers only gradually learned of its existence. As winter turned to spring, Rove would occasionally add other guests. For a Republican, there was no greater call to duty than an invitation from Rove to join the Breakfast Club.

King Karl, ruler of a vast domain, was held in awe by all (except Bush, who from time to time referred to his chief political adviser as Turd Blossom). Rove had never stopped campaigning since the 2000 squeaker. From the moment he walked into the White House in 2001, he had been building the Republican base, the vast Red State army of evangelicals; flag-waving small-town and rural American Dreamers; '60s-hating, pro-death-penalty, anti-gay-marriage social conservatives; Big Donors—the new Republican majority, or so Rove hoped. A steady wave of e-mails (appropriately studded with Rove-isms), notes, photos, anniversary cards and White House Christmas-party invitations stroked the faithful. But discipline was the key: Rove set up a reporting system designed to hold accountable party bosses and volunteers alike. He created the mystique of an all-seeing, all-knowing boss of bosses; if the emperor had no clothes, no one particularly wanted to find out.

A Rove colleague called him "five-dimensional." His friends as well as his enemies described him as generous, crude, charming, repellent, thoughtful, vindictive, funny, mean, brilliant and foolish. Plump and balding, a jolly joker, he could be savage. In Esquire magazine, writer Ron Suskind recalled sitting outside Rove's office waiting for an interview to begin. Inside, he wrote, he could hear Rove bellowing at an aide, "We will f--- him. Do you hear me? We will f--- him. We will ruin him. Like no one has ever f---ed him!" (A White House spokesman has said that Suskind has a "hyperactive imagination.") But Rove was well aware of his reputation and cultivated it. On Halloween 2003, a NEWSWEEK reporter teased Rove for not wearing a costume. "I'm scary enough," he replied.

Rove made little attempt to hide his feelings. Poking his head into the crowded press cabin on Air Force One during a trip on a frigid day in January, he snarled, "Weenies!" In December 2003 Rove's joy at the prospect of systematically destroying Dean was plain for all to see. After the capture of Saddam Hussein, the president's approval rating rose to 63 percent. As Dean continued to fulminate, as reporters no longer described his bluntness as "refreshing" and instead began the old gotcha game, jumping on the green governor's "gaffes," Rove & Co. watched as Dean's negative rating climbed to 39 percent.

Other advisers worried about too much of a good thing. Too much Republican gloating over a Dean candidacy might make the Democrats wake up. "We don't want to tip this thing too far," McKinnon, the campaign's chief media man, fretted in December. "Our concern is that it will collapse on him." But Rove didn't seem concerned. John Kerry had been the presumptive front runner back in the spring of 2003, but by autumn he was not even a blip on the radar screen. At strategy sessions of the Bush-Cheney campaign he was a "nonentity," recalled one Bush adviser. In October, Rove had said that Kerry had "p---ed away every advantage of the front runner." Wes Clark? "Imploded," Rove concluded. Joe Lieberman and John Edwards? "Nowhereville!" he exulted. (Most of the BC04 staff figured Edwards would be the toughest foe, but the North Carolina senator couldn't seem to raise money or get noticed.) Only Dick Gephardt, Rove thought, still had a chance, and not much of one. Rove was so convinced that Dean would be the president's foe in the general election that he began making small wagers around the White House, betting hamburgers that Dean would prevail.

As the holidays approached, the Bush White House was as jolly as Rove. On Dec. 20 the Bush daughters, Jenna and Barbara, both college seniors, decided to hold a blowout for their friends in the Executive Mansion. Jenna, a young lady with her father's eye for a good time, had heard about a band from Nashville that was a big favorite at Southern good-ole-boy fraternity parties. The band, formally called the Tyrone Smith Revue, was better known as Super T. The bandleader, Tyrone Smith, would appear for the second set wearing a red cape and a bright blue jumpsuit emblazoned with a giant T.

The Tyrone Smith Revue set up in the East Room, usually used for press conferences. Shortly after 9, when the drinks were flowing and the kids were starting to glow, Super T swung into "Shotgun" and summoned the president, the First Lady and the twins onto the stage. "I want the Secret Service to stay back!" he cried. "I'm taking over now!" Super T began to instruct the First Family in a dance called the Super T Booty Green. ("Put your hands on your knees. Bend over. Shake two times to the right, shake two times to the left.")

The First Family got right down. The crowd erupted. Super T picked up the beat; he later recalled hearing a familiar voice cry, "Go, Super T!" He looked back to see the president of the United States hollering and shaking it like in old times at the Deke House. Laura Bush gently put her hand on the president's elbow; the frat brother subsided; the chief executive returned to duty.

The Bushes went to bed that night at 11:30, about two hours after the president's usual bedtime. As he dozed off, or tried to, a conga line twisted along the red carpet he usually walked down for formal press conferences. (Before the president retired, Super T offered to play at the Inaugural. Bush just grinned.)

A War President in a War Without End

President Bush badly needed a break. Since 9/11 he had been obsessed. He began every morning by getting briefed on the so-called Threat Matrix, the CIA analysis of the threat of another terrorist attack. He saw himself as a war president in a war without end. "Terrorists declared war on the United States of America," Bush told audiences over and over during the fall of 2003. "And war is what they got!"

Some of his friends thought they saw less of his puckish humor, more of his impatience. The harder the choices, the worse the news, the more chaotic the world, the more stubbornly Bush demanded order in his own life. The onetime hard-drinking party boy was almost ascetic in his discipline: about getting exercise, about getting enough sleep, about having meetings start on time. He nicknamed his own chief of staff, Andy Card, "Tangent Man," for wandering off the subject. It was teasing with a hard edge. "He pays very close attention to his schedule, and if I'm not doing my job of monitoring his schedule, he disciplines me," said Card. All meetings started on time at the White House, or early. There all employees understood the Bush code: "Late is rude."

At the 7:30 a.m. meeting with his staff, the talk increasingly turned to politics as the election year neared. Depending on what he had heard earlier at his threat briefing, Bush could be moody. "You can tell by his tone if he wants the long version or if he wants the short version," said an aide. Sometimes Bush was blunt: "Y'all think this is worth wasting the president's time over?" he would ask when some minor matter came up. Rove was slowest to get the message. For all his political fingertips, Rove was obtuse in his inability, or unwillingness, to read the facial expressions of others. He would sometimes vex Bush by going on too long at meetings. "Karl sometimes doesn't get the signal," said the aide. Or maybe he was just obstinate.

Rove was constantly pushing the president to do more fund-raising. When it came to campaign finance, Rove believed in the Colin Powell Doctrine of Overwhelming Force—i.e., bury the enemy. In 2000 Bush had become the pre-emptive nominee by raising an astonishing war chest of more than $60 million before the campaign began. This time Rove wanted to have at least $150 million on hand to unleash a crushing ad blitz against the Democratic nominee, the minute one emerged.

The president, a homebody, loathed the fund-raising trips. "Another trip?" he would gripe as an aside to Card. Well, how about Laura? Rove would ask. "You will have to talk to the First Lady," Bush would teasingly grumble. "I'm not gonna mention that to her."

But in fact Laura Bush was, in her perfect-wife way, a good soldier. Again and again that fall and the following spring, the First Lady of the United States (FLOTUS, in White House speak) set off on Executive One Foxtrot, traveling under the Secret Service code name Tempo, with a hairstylist and a clutch of guards toting P90 submachine guns. On one trip, FLOTUS's press secretary, Gordon Johndroe, carried a small black case that looked like the bag the president used to carry the nuclear codes. "It's our football," joked Johndroe. The case contained the First Lady's makeup.

President Bush did not like to memorize lines. Mrs. Bush would smilingly rehearse them and speak them that night, word for word, as she posed with fat cats around the country. "We have a special treat for you tonight," her hosts would announce. The First Lady would come into the audience and stop at every table for a photo. It was a routine, repeated in country clubs and upscale hotel ballrooms coast to coast. Laura was unflagging. "She's tougher than the president," said one friend. "I've never seen her cry." She rarely complained, and took solace in small pleasures. After one particularly grueling day of meeting and greeting, she arrived at the Brentwood, Calif., home of a top GOP fund-raiser, Brad Freeman. Concerned that the claws of their cat, Ernie, might scratch up the White House furniture, the Bushes had given their aging six-toed tabby to Freeman to take care of. Spotting Ernie, Laura swept the old fat cat into her arms. "Oh, Ernie!" she cried. "Do you remember me?" She looked over at Mercer Reynolds, the chief fund-raiser for the Bush-Cheney campaign. "Oh, he remembers me!" she exclaimed, a bit wistfully, to Reynolds. ("I'm not sure Ernie really remembers much of anything," said the moneyman, as he later recalled the scene.)

Laura had always been protective of the twins. But they were 22 years old now, about to graduate from the University of Texas and Yale, and attractive young women couldn't help but humanize the campaign. On the other hand, getting the girls involved could prove to be a disaster. In early winter, Gordon Johndroe went to Mrs. Bush with an interview request from a fashion magazine. He expected her to say no, as she always did, but instead she just said, "Why don't you call and ask the girls first?" The campaign had some reason to be anxious about the twins. Their partying had been in the papers, at first in scrapes about underage drinking, more recently when Barbara, a Yale senior, had been photographed by the tabloids dirty-dancing with a 25-year-old Ecuadoran playboy who had a few outstanding arrest warrants. Barbara was hanging off his leg. "Like a dangling chad," observed the New York Daily News. The girls ultimately decided to do a fashion shoot in ball gowns with Vogue magazine.

Bush-Cheney campaign manager Ken Mehlman was piloting his black Audi A4 home from the airport when he heard the otherworldly scream. He was giving Communications Director Nicolle Devenish a lift, and they were listening to the results of the Iowa caucuses. Howard Dean had just finished giving his concession speech/pep talk when he let loose with a primal yowl. "Holy s—t!" cried Devenish. "Listen to that guy!" Mehlman exclaimed, "He's going crazy!" Across the Potomac River at Bush-Cheney headquarters in Arlington, Va., Sara Taylor, the deputy strategy chief, was watching TV in her office. She cried out, "He just went crazy!" Adman Mark McKinnon realized that the former Vermont governor had just made the most amazing contribution to the Bush-Cheney collection of Dean speech clips, the file entitled "Dean Unplugged." Sadly, he knew it was also the last, and that the collection was now worthless. "Stick a fork in him," McKinnon told himself.

Only Rove held out hope. Dean still had an organization, said Rove, who placed great weight on organization. Bush, who knew Dean's volatility from working with him as a fellow governor, had always suspected he would flame out. Now Bush needled his political guru about his hamburger wagers. Want to double your bets? the president asked. Dean still has money, Rove grumbled. Lots of candidates lose Iowa and come back. "This guy ain't coming back," Bush said, laughing.

Five nights later, on Jan. 24, Bush and a few of his political advisers lounged on couches in the West Sitting Hall, a living-room space in the residence with an elegant fan window. Bush was sitting in an armchair, sipping a non-alcoholic beer. He was dressed in a tuxedo and cowboy boots; later that evening he would make a few jokes at the Alfalfa Club dinner, an annual, mostly male gathering of Washington movers and shakers. Barbara and some Yale friends were wandering around. Barney, Bush's terrier, was asleep on a couch.

The mood was mellow. To be sure, the politicos arrayed on the couches, Mehlman and McKinnon and top moneyman Reynolds, were sorry to lose Dean. Mehlman remarked that Dean didn't have any money left. "I thought he was supposed to have lots of money," said Bush. The others shrugged. They wondered: where did all the money go? Landon Parvin, a speechwriter who had been brought in to write Bush's jokes, didn't have the sense that the men in the room were particularly worried about John Kerry. Someone pointed to Kerry's long Senate record, rich with liberal votes and flip-flops. Someone else took a swipe at Teresa Heinz Kerry. She won't play well on TV, the man said. Parvin threw out a question: whom would they not like to see on the ticket as the vice presidential candidate? Bush said it didn't really matter. Lloyd Bentsen, the popular Texas senator who ran with Michael Dukakis in 1988, hadn't helped much in his own home state, said Bush.

Not everyone was so sanguine about the shape of the race. Other politicians had underestimated Kerry, the pundits and professionals kept warning. Bush would be foolish to make the same mistake. Around Washington, the Wise Men began muttering about the lack of a clear message from the Bush White House. A low but steady whine could be heard from the permanent Republican establishment, the ghosts of GOP administrations past—men who had worked for Nixon, Reagan and Bush's father, "41," as he was known (the 41st president; George W. Bush was "43," the 43rd president). President Bush boasted that he never read the newspapers, but these gray-haired ex cabinet secretaries and former top advisers, most of whom had become consultants and lawyers and lobbyists, inhaled The New York Times and The Washington Post over breakfast and listened to NPR or the off-color but clever radio talk show "Imus in the Morning" on the way to work. They were creatures of the old mainline media, which was, out of "liberal bias" or just straight reporting, growing increasingly skeptical about the Bush presidency. Over lunch at the Metropolitan Club or up at the expense-account eateries on Capitol Hill, they wondered aloud: where was Karen Hughes when the president needed her?

Over 6 feet tall, with frosted hair and a strong, flat Texas accent, Hughes had been the chief message maker and enforcer in the 2000 campaign and for the first two years of the Bush presidency. Then she had retreated to Texas to be able to spend more time with her teenage son, who had loathed living in Washington. Hughes had a knack for parroting Bush's tone and voice, for "channeling" him. She also softened his hard edges. In 2000 Hughes had gently prodded Bush to play the "compassionate conservative." After she left, the Bush watchers detected a hardening in the Bush line, which they attributed to Rove, who was always reaching out to the party's true believers. Hughes had jockeyed some with Rove for power, but by and large the two forceful figures had produced a consistent message (helped by a boss who insisted on staying "on message"). Hughes had policed the wayward and zipped loose lips. When she was communications director, talking out of line would earn you "a size 11 shoe up your a--," according to a former White House official. Journalists were awed by her industrial-strength spin and no-prisoners approach to the chaos of the White House press room. They had nicknamed her Nurse Ratched, after the iron woman who ran the psycho ward in "One Flew Over the Cuckoo's Nest."

From her home in Austin, Hughes still weighed in on key speeches and decisions, but there was no one with quite her clout running the White House communications operation. Her successor, Dan Bartlett, a former Future Farmer of America, had gone to work for Rove at the age of 22. He was regarded as "too much Karl," and hence "political." It may seem obvious that the communications director would be political, but in Bushworld advisers were supposed to stay in their lanes. The White House "message" was not just political; indeed, the leader of the free world did not want to be seen as a poll-watching politico. Rove was thought by some White House staffers to have a bit of a tin ear, to lean too hard, to reach too far to cater to his prized right-wing base. (Even Bush would crack, "That idea's so f---ing bad it sounds like something Rove came up with.")

Indeed, no one seemed to know who was in charge of the message. Rove? Bartlett? Hughes from the shadows? Bush himself? Obsessed with message discipline, the president would blow up about leaks. "I'm p---ed," he told his staff when word leaked out that he was planning to roll back steel tariffs, imposed in 2002 to give an economic lift to manufacturing (and key swing) states like Pennsylvania and West Virginia. What, exactly, was the White House message? Was the tone supposed to be cautious or bold, funny or serious? Nobody seemed to know for sure. The various admen hired by the campaign made fun of the ponderous, research-driven, tone-deaf messages handed down from on high. One original Bush-Cheney slogan was supposed to be "President Bush: Because the Stakes Are So High." The ad guys circulated an e-mail mocking the slogan as "President Bush: Because the Steaks Are on the Grill." The slogan was quickly dropped.

How to Sell Bush

It was Mark McKinnon's job to figure out how to sell Bush. McKinnon was the BC04 media man, in charge of the air war, the multimillion-dollar campaign to build Bush up and tear Kerry down. McKinnon was a bit of a misfit at the anonymous, faceless Bush-Cheney headquarters in Arlington. (To avoid truck bombs, the campaign had chosen a building set well back from the street; no sign marked the door.) The BC04 offices could have been occupied by an insurance company: rows of cubicles filled with tidy people. The dress code was by and large Brooks Brothers drab, though there did seem to be an unusual number of young blond women whose trust funds financed snappy or discreetly elegant wardrobes.

McKinnon framed his office doorway with twinkling lights. Inside he placed a Lava lamp and short, squat candles. He wore red blazers and cowboy hats. His advertising team joked that he had "metrosexual moments." Matthew Dowd, the campaign's pollster and McKinnon's partner in the "Strategery Department" (named after a late-night comedy show's parody of President Bush mangling the word "strategy"), was also a little out of place in such a button-down, fixed-smile environment. The Yeats-quoting Dowd was a chronic pessimist. (Taped to his office wall was Dowd's favorite Yeats quote: "Being Irish, he had an abiding sense of tragedy which sustained him through temporary periods of joy.") Unlike the suits all around him, Dowd usually wore cargo pants. The mood at Bush-Cheney headquarters was supposed to be relentlessly upbeat, in a corporate sort of way. Some aides noticed that unfavorable newspaper stories seemed to be omitted from the package of news clips distributed around the office. The correct mood was ordained by King Karl. "Fabulous," Rove always said, when asked how things were going. "Everything's fabulous." Oddballs, particularly artsy ones, felt a little insecure. (When deputy campaign manager Mark Wallace listed an obscure architecture book as his favorite on a media questionnaire, his girlfriend, Communications Director Devenish, scolded, "Honey, you can't put this down!" He filled in "Bush at War" instead.)

Dowd was a little melancholy and normally laid-back. McKinnon called him the "Valium" of the campaign. He stood in stark contrast to Ken Mehlman, the campaign manager, who was so wound up his lip trembled. His head bursting with arcane statistics (the staff called him Rain Man, after the Tom Cruise movie), Mehlman prided himself in efficiency and low overhead. He wanted to minimize the "burn rate" for campaign funds. The ad boys were always squawking that their ad budgets were being cut and their expense accounts scrutinized.

For the first big ad buy in March, Dowd wanted to showcase Bush displaying true grit. McKinnon believed that voters wanted a story line, an arc, that would portray the president struggling with and overcoming adversity. Dowd focus-grouped an ad, called "Safer, Stronger," that depicted grim images, including firefighters carrying a flag-draped coffin. "When you talk about a 'day of tragedy,' the dials just go boom!" said McKinnon, throwing his hand in the air.

But convincing the Bushes took some doing. In late February, Bush invited his campaign inner circle to the White House residence for the first preview of their coming advertising assault. Bush, Rove, Bartlett and Laura Bush were all there. McKinnon was nervous. "It's like opening on Broadway," he later said. The Democratic race had shifted at warp speed. All the anti-Dean ads were out the window. Alex Castellanos, a veteran adman, had written a particularly effective one, showing an empty chair in the Oval Office and subtly raising the question of whether Dean belonged there. But Kerry did seem presidential. The Bush campaign wasn't ready to bash Kerry—yet. First they needed to run a few spots building up their own man.

There wasn't much time to work if the president was displeased with what McKinnon and Dowd had to offer. The screening, technologically speaking, was a disaster. Fumbling with the DVD machine, McKinnon kept bringing up the wrong spot, and he couldn't shut off the background music when it failed to suit the ad on the screen. The basic message of the first ad was "Safer, Stronger," but Bush worried it was too pessimistic. It opened by talking about a poor stock market and the ravages of 9/11. A second ad, "Tested," echoed similar themes and ended with a shot of the charred World Trade Center. These were not problems of Bush's creation; nonetheless, he was concerned about the somber tone. Bush was determined to be positive, upbeat. For a moment his advisers feared that they would have to scrap "Safer, Stronger." But Bush backed off, and with a few small tweaks the 9/11 ads were greenlighted.

The ads, when they were first screened on March 3, caused a dust-up. Reporters fired questions at Mehlman and the others at Bush-Cheney headquarters. Wouldn't some voters think the campaign was exploiting 9/11? Wasn't the coffin a little much? By the next day some 9/11 widows were criticizing the spots. The mainstream press turned harshly critical. BUSH CAMPAIGNS AMID A FUROR OVER ADS, read the headline in The New York Times. A 'SHOCKING' STUMBLE was NEWSWEEK's headline.

McKinnon and Dowd were ecstatic. At a strategy meeting the next day—the same morning the Times headline appeared—they joked about how they could fan the flames. Controversy sells, they said. It meant lots of "free media"; the ads were shown over and over again on news shows, particularly on cable TV. The "visual" of the rubble at the World Trade Center was a powerful reminder of the nation's darkest hour—and Bush's finest, when he climbed on the rock pile with a bullhorn. What's more, the story eclipsed some grim economic news, low job-creation numbers released by the Labor Department. McKinnon and Dowd had commiserated over the job report in Dowd's office. They knew that the strength of the economy would be the best single predictor of the election's outcome. "That was a moment when we kind of gulped and said, 'Oh, man'," McKinnon later recalled.

At that Saturday's Breakfast Club, they were still laughing about the ad flap. (Rove had cooked eggs, bacon and some tasty venison sausage.) Dowd told the group they had received $6 million to $7 million worth of free ad coverage. "Unfortunately, we've been talking about 9/11 and our ads for five days," Dowd deadpanned at a senior staff meeting. "We're going to try to pivot back to the economy as soon as we can."

There were chuckles all around. But the group was already feeling ground down. The press coverage seemed unusually intense for such an early stage of the campaign. Ken Mehlman thought it felt like October, and it was still March. Shortly after the ads hit the air, McKinnon stopped in at Nicolle Devenish's office to find her shivering, sweating and wrapped in a blanket. McKinnon walked into Dowd's office. The lights were off. He glanced down and found Dowd asleep on the floor, passed out cold. "We're gonna kill everybody by June," McKinnon thought to himself.

Trench Warfare

'The Interregnum': After the primaries, Kerry was cranky and his campaign began to drift. The Bush war room wanted to 'define' him, and knew how to get under his skin.

A Petulant Kerry

Elise Amendola / AP

Kerry tried to forget the campaign