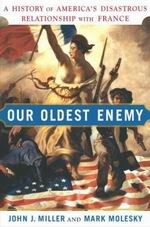

Our Oldest Enemy: A History of America's Disastrous Relationship with France

I first saw the authors on FoxNews with Tony Snow. I was fascinated as they explained the role of France through the decades past. Knowledge worth having and remembering.

An excerpt follows:

Our Oldest Enemy: A History of America's Disastrous Relationship with France

By: John J. Miller and Mark Molesky

Introduction

“A War Without Death”

When French President Jacques Chirac learned on September 11, 2001, that terrorists had toppled the World Trade Center, smashed a fiery hole into the side of the Pentagon, and plunged a plane full of passengers into a Pennsylvania field, he broke off a tour of Brittany and rushed back to Paris. “In these terrible circumstances,” he said, “all French people stand by the American people. We express our friendship and solidarity in this tragedy.” A week later, he stood next to George W. Bush in the Oval Office. “We are completely determined to fight by your side,” he promised the president. “France is prepared and available to discuss all means to fight and eradicate this evil.” The next day, he became the first foreign head of state to visit Ground Zero in Manhattan.

Chirac’s words and actions were both strong and stirring. They were also expected from a leader whose country had survived the ravages of the twentieth century in large part because of the leadership and sacrifice of the United States. On September 12, France’s newspaper of record, Le Monde, added its support with a front-page editorial featuring the headline “Nous Sommes Tous Américains”—We Are All Americans. The U.S. media turned this simple and poignant phrase into a rousing refrain. America’s oldest ally was reasserting its close historical and cultural ties in a moment of national catastrophe.

Or so it seemed. From the beginning, cracks in Franco-American relations were apparent. As Bush began to speak of a war on terror—“a new kind of war,” he called it—Chirac expressed reservations. “I don’t know whether we should use the word war,” he cautioned during his visit to the White House on September 18.

Over the next year and a half, semantic disagreements gave way to open conflict as France waged a vigorous campaign of obstruction and harassment against the United States and its war on terror. As the Bush administration set out to take preventative action against the tyrants, organizations, and foot soldiers who had already murdered thousands and were busy plotting future attacks, France was generous with aid and information. But when the United States decided to end the outlaw regime of Saddam Hussein in Iraq as well, Chirac and his government did everything in their power to thwart American efforts.

Not content with simply voicing their opposition, the French actively fought the Americans at every turn. They delivered condescending lectures on the arrogance of the United States and the sanctity of Iraqi sovereignty. They insisted that the Bush administration proceed only with the approval of the United Nations—and then threatened to use their veto power on the Security Council to block effective military action. They went so far as to form a new political axis with Germany and Russia and tried to rally the world against the American resolve. They insulted and bullied countries that chose to defy Paris and support the United States. They publicly declared the nations of Africa to be opposed to an invasion of Iraq, though their claims were based on pledges that had not in fact been made. In a provocative and totally unprecedented move, they endangered a cornerstone of Western security by attempting to block a request from fellow NATO member Turkey for defensive military equipment to be used in the event of an Iraqi attack. France’s entire foreign policy seemed driven by belligerence toward the United States.

Chirac’s top deputy in this anti-American offensive was Foreign Minister Dominique de Villepin. An amateur poet and historian with oily good looks and a condescending manner, Villepin became the leading French spokesman at the UN and in the media. For all his charms, he had great difficulty hiding the deep resentment he felt toward the United States and its policies. While American soldiers and their allies were battling Saddam’s henchmen inside Iraq in the spring of 2003, Villepin could not even bring himself, under direct questioning, to say that he hoped for a U.S. victory.

Chirac and Villepin were hardly alone in their anti-Americanism. In a speech to the French legislature, Prime Minister Jean Pierre-Rafarrin scolded Americans for their “simplistic view of a war of good against evil.” One wonders whether the prime minister views America’s crusade to drive Hitler from France sixty years earlier in a similar light. Although Rafarrin chose not to address such complexities, he did add a quintessentially French flourish to his remarks: “Young countries have the tendency to underestimate the history of old countries.” Americans have become accustomed to such patronizing from the French. In this instance, however, the prime minister might have benefited from a history lesson. After all, which country is older? The one with a durable and long-lived constitution or the one that currently calls itself the Fifth Republic? Perhaps the youthful regime of France was guilty of underestimating its older, wiser, and more experienced democratic cousin.

Then there was the matter of what Le Monde really meant when it declared “We Are All Americans.” This much-celebrated headline sat atop one of the most-cited but least-read newspaper editorials ever written, for beneath that catchy phrase was an anti-American diatribe of extraordinary virulence and rage. Penned by publisher Jean-Marie Colombani, it worried that the United States would turn “Islamic fundamentalism” into “the new enemy.” After the Oklahoma City bombing in 1995, wrote Colombani, Americans had succumbed to an “anti-Islamic reflex” consisting of “ridiculous, if not downright odious” behavior. He further asserted that 9/11 had occurred because the United States dominates a world “with no counterbalance.” The terrorist atrocity was the predictable result “of an America whose own cynicism has caught up with it” in the person of Osama bin Laden, whom he interpreted as the villainous invention of the Central Intelligence Agency. Anything but a declaration of solidarity, the famous editorial was constructed around a particularly ugly and outrageous slander: “Might it not then have been America itself that created this demon?”

Credited in the world press with a sympathy for America that it had not expressed, Le Monde made certain in the days to follow that none of its readers would misinterpret its true beliefs. “How we have dreamt of this event,” wrote the eminent intellectual Jean Baudrillard, referring to 9/11. “How all the world without exception dreamt of this event, for no one can avoid dreaming of the destruction of a power that has become hegemonic. . . . It is they who acted, but we who wanted the deed.” Colombani also did his best to make sure no one in the future would mistake him for an admirer of the United States. In subsequent writings, including a book called Tous Américains? (All Americans?)—in which he retreated from his original headline by adding a question mark—the illustrious publisher stooped to present an old and vicious caricature of America as a country controlled by crazed Christian dogmatists who excelled at oppressing their black neighbors. He further argued that the United States was hypocritical to protest the consequences of Islamic radicalism when it still embraced that supposedly primitive instrument of legalized brutality, the death penalty.

Although millions of Americans found the behavior of the French exasperating, many initially responded in a characteristically American way: with humor. “You know why the French don’t want to bomb Saddam Hussein?” asked television comedian Conan O’Brien. “Because he hates America, loves mistresses, and wears a beret. He is French, people.” Every evening seemed to bring a new late-night laugh. “I don’t know why people are surprised that France won’t help us get Saddam out of Iraq,” joked Jay Leno. “After all, France wouldn’t help us get the Germans out of France.” Even politicians joined in: “Do you know how many Frenchmen it takes to defend Paris?” quipped Congressman Roy Blunt of Missouri. “It’s not known. It’s never been tried.” Jokes were a way for Americans to express their frustration with the behavior of a country they considered a friend.

As the quarrel intensified, however, American feelings toward the French shifted from bemusement to betrayal. From a cafeteria in Congress to diners and eateries across the country, french fries were transformed into “freedom fries.” Restaurant owners poured bottles of French wine down drains and promised to stock only American vintages or those from countries that supported the war on terror. On the popular television program The O’Reilly Factor, host Bill O’Reilly launched a nationwide and much-publicized appeal to boycott French products. Internet sites posted long lists of brand-name items owned by French companies: Bic, Evian, Michelin, Perrier, and Yoplait. The U.S. presence at the renowned defense-industry confab, the Paris Air Show, was really more like an absence (as a French deconstructionist might say). The economic impact was immediate. French wine exports to the United States dropped like guillotines during the Reign of Terror. American tourists avoided France, where government officials calculated losses in the billions. Before the terrorist attacks of 2001, 77 percent of Americans held a favorable opinion of France and a mere 17 percent held an unfavorable one. In March 2003, on the eve of the invasion of Iraq, these feelings were reversed. Only 34 percent of Americans saw France in a positive light, while fully 64 percent viewed it negatively.

In the United States, earnest pundits lamented the rift between the two countries. “Franco-American friendship goes back a long way,” warned Kevin Phillips on National Public Radio. If the bitterness continued, it might erase a cherished legacy of goodwill and harmony. “We run the risk of losing this long friendship, a history built up over time and adversity,” wrote Josephine Humphreys in the New York Times. “Do we really want a divorce?”

Such sentiments assume, of course, that there had been a marriage in the first place—a marriage allegedly consummated when France rushed to the aid of desperate American colonists during their War of Independence. That’s where the oft-told story of Franco-American friendship usually begins, with tributes to the valor and idealism of the Marquis de Lafayette, the gallant aristocrat who offered his services to General Washington and the American cause. Within a few years of his arrival, the French provided decisive naval support at the battle of Yorktown, securing American liberty. Next comes the Louisiana Purchase of 1803, commonly understood as a benign transaction in which Napoleon generously sold vast tracts of North American real estate at rock-bottom prices to his friend Thomas Jefferson. In the decades to follow, the French aristocrat Alexis de Tocqueville toured the United States and gazed in wonder at its political achievements, leaving the impression that it was the French who had discovered the genius of American democracy. Later in the century, France made a gift of the Statue of Liberty to its sister republic and became America’s tutor in the ways of art and culture. In the twentieth century, American doughboys fought in the trenches beside French troops in the First World War and symbolically repaid America’s debt to Lafayette and his country. A generation later, GIs valiantly stormed the beaches of Normandy, liberated freedom-loving France from the Nazis, and, as their reward, enjoyed the gratitude of comely French maidens. During the Cold War, the United States and France stood shoulder to shoulder as they stared down the Soviet menace. Sure, Charles de Gaulle could be prickly and pompous at times, but he remained a steadfast ally of America when the chips were down. And in the early 1990s, when Saddam Hussein invaded Kuwait, the French once again went bravely into battle alongside their American cousins.

Isn’t that how the story goes? Deep down, underneath their berets and black turtlenecks, don’t the French really love us?

Au contraire. This familiar and comforting narrative can be found in our history books. French politicians eager to advance their country’s interests have nurtured it. American statesmen have been seduced by its charms. Yet this feature of our popular imagination is in fact a figment of our imagination. The tale of Franco-American harmony is a long-standing and pernicious myth. The French attitude toward the United States consistently has been one of cultural suspicion and dislike, bordering at times on raw hatred, as well as diplomatic friction that occasionally has erupted into violent hostility. France is not America’s oldest ally, but its oldest enemy.

The true story of Franco-American relations begins many years before the American Revolution, during the French and Indian Wars. Lasting nearly a century, these conflicts pitted the French and their Indian comrades against seventeenth- and eighteenth-century American colonists. French military officers used massacres as weapons of imperial terror against the hardy men, women, and children who settled on the frontier. At the age of twenty-two, George Washington nearly fell victim to one of these brutal onslaughts and was reviled in France as a murderous villain for many years (an opinion sustained by French propaganda and reversed only when the American Revolution made it politically necessary). Amid this tumult, the first articulations of a recognizably American national consciousness came into being. Indeed, America’s first authentic sense of self was born not in a revolt against Britain, but in a struggle with France.

Although the French provided American colonial rebels with crucial assistance during their bid for independence, direct French military intervention came only after the Americans had achieved a decisive victory on their own at Saratoga. The French crown regarded the principles of the Declaration of Independence as abhorrent and frightening. French aristocrats viewed Lafayette with contempt and branded him a criminal for traveling to America against King Louis XVI’s explicit command. The king and his government overcame their revulsion to the young republic only because they sniffed an opportunity to weaken their ancient rival Britain. To be sure, France did become an ally to the colonists for a few years in the late 1770s and early 1780s when American sovereignty served French geopolitical aims. But then the French believed that double-dealing against their erstwhile friends after Yorktown served their interests as well. During the peace talks, France sought to limit American gains because it feared the new nation might become too powerful. If the French had achieved all of their objectives in the Treaty of Paris in 1783, the United States today might be confined to a slender band of territory along the eastern seaboard, like a North American version of Chile.

In 1998, French defense minister Alain Richard declared that “France and the United States never fought each other.” This is manifestly untrue. Within a generation of Yorktown, French and American forces were exchanging deadly fire during the little-known Quasi-War of 1798–1800—during which France earned the dubious distinction of becoming the first military enemy of the United States following the ratification of the Constitution. Shortly before these hostilities, France supplied the United States with its first foreign subversive: French ambassador Edmond Charles Genet, better known as “Citizen Genet.” In 1796, a Genet successor, Pierre Adet, meddled in the presidential election in a desperate but failed attempt to prevent John Adams from becoming commander-in-chief.

During the Napoleonic era, France posed a constant threat to the United States and its westward expansion. Napoleon himself longed to invade North America with a powerful army. He agreed to sell the Louisiana Territory only after suffering a military disaster in the Caribbean and hearing threats of war from Thomas Jefferson. The War of 1812 was very nearly fought against France rather than Britain, and the Monroe Doctrine was written with France clearly in mind. In the 1830s, Andrew Jackson came close to declaring war on France for its persistent refusal to make good on promised reparations for French naval crimes during Napoleon’s reign.

Whenever French politicans want to generate feelings of goodwill among Americans, they invariably appeal to the memory of Lafayette and Yorktown. They neglect to mention the French role in the Civil War, when Napoleon’s imperial nephew supported the South and incited disunion, carried out the first major transgression of the Monroe Doctrine, and engaged in what General Ulysses S. Grant considered acts of war against the United States.

In the twentieth century, France welcomed American help to end the First World War. During the subsequent peace negotiations, however, the French fought the United States over how to treat the vanquished Germans and conceive a postwar world. By rejecting the advice of Woodrow Wilson and insisting on crippling and humiliating reparations, France fatally undermined the fledgling German democracy and planted many of the seeds of the Second World War—a conflict for which the French required another American rescue. Before that liberation could occur, however, American troops landing in North Africa in 1942 encountered stiff resistance from the soldiers of Vichy France. The GIs literally had to fight their way through the French to get to the Nazis.

More than 60,000 Americans who gave their lives in these two world wars lie buried in French soil. Yet it was not long after the Second World War had ended that many in France forgot this sacrifice. Anti-Americanism metastasized as a whole generation of French intellectuals embraced the West’s totalitarian enemy, the Soviet Union. During the Cold War, French misrule in its Southeast Asian colonies made Ho Chi Minh’s Communist movement possible and set the stage for an American debacle. Indeed, if the French had followed the advice of Franklin Roosevelt and granted Vietnam its independence after World War II, the Vietnam War might not have been necessary, and today Vietnam might be a prospering democracy like South Korea.

During the presidency of Charles de Gaulle, France became the source of strife within the Western alliance as it undermined NATO and downplayed the Soviet threat—and even refused to rule out aiming its own nuclear missiles at the United States. In 1986, when the United States obtained positive proof that Libyan strongman Muammar Qaddafi was behind a fatal terrorist bombing in Berlin, the French rejected American requests to let U.S. warplanes fly through their airspace on a mission to retaliate against a sinister forerunner of Osama bin Laden and Saddam Hussein.

At times, Americans have reacted with passionate indignation at French hostility and intransigence. In the 1790s, during the infamous XYZ Affair, the public was outraged when French officials demanded huge bribes from U.S. diplomats. In the 1960s, de Gaulle’s shrill anti-American harangues and his dramatic decision to pull French troops from NATO resulted in boycotts of French products across the United States. Yet the myth of Franco-American friendship remains so tenacious that when each new generation of Americans encounters French enmity, it reacts with shock and disbelief.

The French themselves have harbored considerably fewer illusions. “We are at war with America,” declared François Mitterand shortly before his death in 1996. “A permanent war . . . a war without death. They are very hard, the Americans—they are voracious. They want undivided power over the world.” Indeed, anti-Americanism has deep roots in France, especially among its political and intellectual elites. Fueled by an abiding belief in French superiority, this attitude at times has assumed odd shapes: As a diplomat in Paris in the 1780s, Thomas Jefferson tried to disabuse French thinkers of their strange insistence that North American animals were smaller and weaker than those native to Europe. More often, however, the French have sought to contrast their Old World refinements with what they have regarded as New World vulgarities. As French prime minister Georges Clemenceau put it, “America is the only nation in history which miraculously has gone directly from barbarism to degeneration without the usual interval of civilization.”

Yet the French have been victims of their own illusion: a mirage of grandeur and entitlement based on the belief that because France was once a powerful nation, it should always be a powerful nation. This has produced a national character dominated by nostalgia for a glorious past that simply cannot be recovered. French national decline began in the middle of the eighteenth century and has progressed almost without interruption. The single exception came during the reign of Napoleon, when the French made an audacious and bloody bid for European dominance. Their failure has haunted them ever since. Time and again in the last two centuries, France has refused to come to grips with its diminished status as a country whose greatest general was a foreigner, whose greatest warrior was a teenage girl, and whose last great military victory came on the plains of Wagram in 1809. Instead, it projects a politics of chauvinism and resentment—with much of its animus aimed at the United States, a nation whose rise to prominence in global affairs presents almost a mirror image of French decline.

Indeed, the very word chauvinism derives from the life and attitude of one Nicolas Chauvin, an officer in Napoleon’s Grande Armée who was severely wounded seventeen times during his military service. Years after Waterloo, he refused to give up his fierce loyalty to his former general and the French dream of empire. In time, the French public made Chauvin’s excessive patriotism an object of ridicule and derision. Plays satirized the disfigured ex-soldier and his undying loyalty to the imperial cause. Yet if the French had looked more closely at themselves, they would have seen that Chauvin was less of an eccentric than an exemplar. As French power and influence withered, the French public remained true to the alluring vision of a great and transcendent France—just like Napoleon’s gallant soldier. Unfortunately, a foreign policy built on a fantasy is bound to stumble when it encounters hard realities. Much Franco-American friction over the last century and a half has come from the French reluctance to accept a new role in a democratic world order led by the United States.

But Americans, with all their own cultural insecurities, have more often than not chosen to overlook French arrogance and condescension, preferring instead to revel in France’s considerable artistic and intellectual achievements. From Henry James’s enthusiasm for the subtleties of French manners and conversation to the many African-American writers and musicians who found acceptance and creative inspiration in Paris’s Montmartre and Montparnasse, Americans of taste and discernment have long been drawn to the rich cultural tradition of their European brethren. Even during moments of serious discord, Americans have refused to turn their backs on the great lights of French civilization. The Beaujolais Nouveau may be poured down the drain, but Rabelais, Balzac, and Camus remain on the shelves.

The French often disguise their contempt for America with false affection. In the fall of 2003, former prime minister Lionel Jospin paid the United States a typically backhanded compliment: “The French love America so much that they’d often like it to be different.” This is rather like saying that the French love apple pie so much they wish it were escargot. Although the French masses have welcomed American movies, music, and literature, French elites such as Jospin frequently display xenophobic suspicion of American cultural influences. Take the word email. In 2003, the French government banned it from official documents because of its American provenance. Writers are told instead to use a made-up word, courriel. Although the word mail actually entered the English language by way of the Norman invasion, the French seem to believe that Anglo-Saxon usage over the course of a millennium has corrupted it. The French have even allowed their cultural protectionism to assume violent forms. When a mob of vandals attacked a McDonald’s restaurant in the south of France in 1999, Chirac applauded.

Throughout the recent differences over Iraq, the French have continued the charade of pretending that they are America’s best friend—“its ally forever,” as Chirac said in the wake of September 11. But true friends and allies of the United States do not behave the way the French did. Despite the British public’s misgivings about the wisdom of invading Iraq, Prime Minister Tony Blair acted with a solid appreciation of America’s positive role in the world and a firm understanding of common values and mutual interests. Where Britain has transformed itself from an old enemy into a true ally, France has failed to do the same. Perhaps this is simply a reflection of French political experience. Historically dominated by a pendulum swinging between the extremes of right and left—the very concepts of “Right” and “Left” come from the French Revolution—modern France simply has not developed a sufficiently deep foundation in liberal democracy that would lead it to believe, along with the United States and Britain, that a successful foreign policy can be based on common ideals. The hypernationalist French continue to jockey for global supremacy much as they did three hundred years ago. And while it is no sin for a government to pursue a foreign policy of national interest—all nations owe this to their citizens—the French have failed to realize that the United States does not pose and, in fact, never has posed a threat to their country. In the words of the French novelist and critic Alphonse Karr: Plus ça change, plus c’est la même chose. The more things change, the more they stay the same.

<< Home